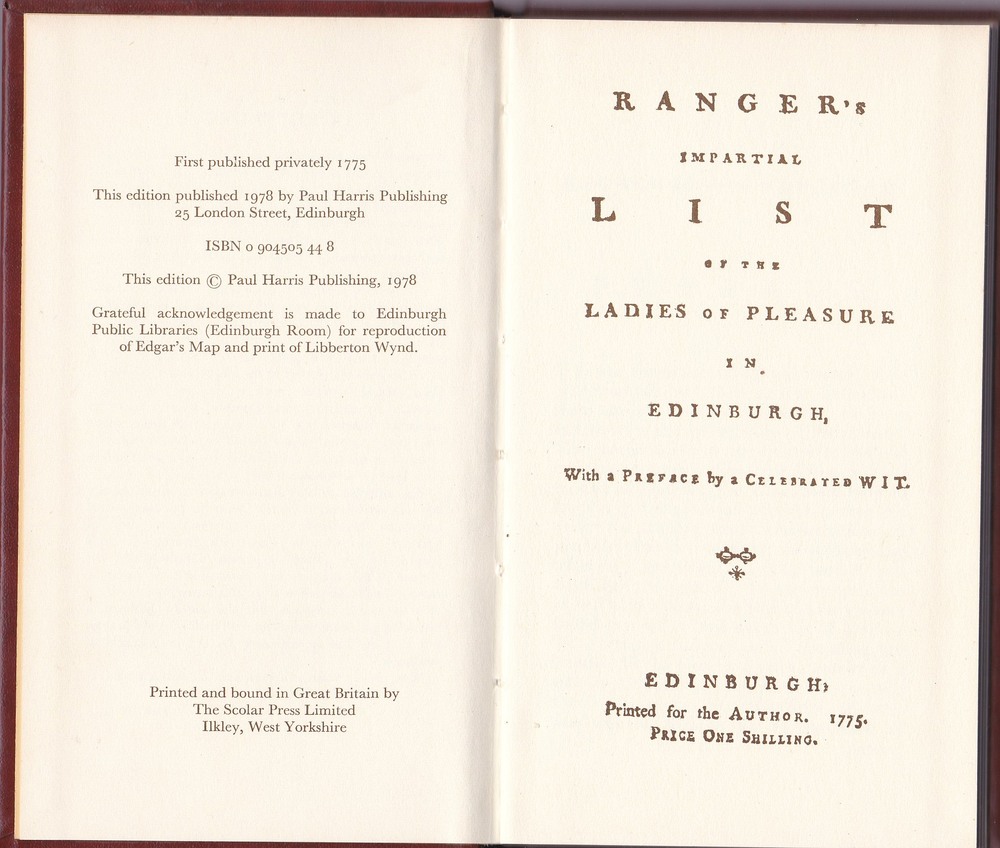

In the late 18th century, tourists seeking carnal pleasure in Scotland’s capital city Edinburgh had a handy guidebook to start with. It detailed the names, ages and specialties of sixty-six of Edinburgh’s foremost working girls and where to find them. Unlike the infamous Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies—an annual directory of London prostitutes—that ran for four decades, the Ranger’s Impartial List of Ladies of Pleasure was published only once, in 1775.

Although the book was published anonymously, it was later revealed that the man behind the meticulous research was James Tytler, a perpetually debt-ridden writer and balloon enthusiast who later went on to become the editor of Encyclopædia Britannica, contributing hundreds of articles and almost singlehandedly enlarging the volume to more than three times its size.

James Tytler was born in 1745 in Forfarshire (now known as Angus) to a clergyman of the Church of Scotland. Tytler originally planned to follow in the footsteps of his father, but unable to accept the strict doctrines, he turned to medicine instead. To raise funds for his education at Edinburgh University, Tytler worked as a surgeon on a whaling ship for a year. After he graduated, Tytler decided he didn’t want to practice medicine, and instead opened a pharmacy in Leith, near Edinburgh. When that enterprise failed, Tytler dabbled in scientific writing, toiling for meager fees for small publishers and booksellers who employed him to abridge and rewrite several volumes.

Tytler lived miserably and carelessly, and drank heavily, but he had this outstanding ability to produce articles on demand at short notice. Once a Scottish gentleman requiring a brief treatise on a historical subject, tracked him down to a small, filthy attic where he was hiding from his creditors and family. Tytler heard what was needed from him, then asked his landlady to bring him paper, pen and ink. Then using an upturned washbasin as his desk, Tytler scribbled away for two hours, at the end of which he produced a complete work that anyone would have had a hard time believing if he was told that it was written by someone who was roused from sleep, with no prior notice and with fumes of alcohol still lingering in his breath.

James Tytler, the 18th century content mill.

It was this gift he had that helped Tytler find work. He produced a volume titled Essays on The Most Important Subjects on Natural and Revealed Religion, wrote a great number of medical treatises and published a short-lived periodical called A Gentleman’s and Ladies’ Magazine. He also compiled the Ranger's Impartial List of the Ladies of Pleasure, using the pseudonym “Ranger” to save himself and his family the embarrassment.

It was a short book, about forty pages long, with a brief description of each women. A typical entry reads:

Miss Sutherland, Back of Bell’s Wynd

This Lady is an old veteran in the service, about 30 years of age, middle sized, black hair and complexion and very good teeth, but not altogether good-natured.

She is a firm votary to the wanton Goddess, and would willingly play morning, noon, and night.

As a friend, we will give a caution to this Lady, as she has a habit to make free with a gentleman’s pocket, especially when he is in liquor.

Not much is known about the circumstances that led him through the depraved path, or exactly how Tytler collected the information presented in the book. Was the book based on his own experiences? Tytler certainly didn’t have the money for such hedonistic pursuits. He had six mouths to feed, and was scarcely making ends meet.

According to the Scotsman, Tytler planned a follow-up list dealing with the ladies of Glasgow, but decided to scrap the idea after the first book left him exhausted.

James Tytler eventually found employment under printers Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell, who were at that time compiling an English encyclopedia as an answer to the French Encyclopédie. Macfarquhar and Bell rescued Tytler from the debtors' sanctuary at Holyrood Palace, and put him to work at only seventeen shillings per week. Tytler, accustomed to working for cheap, was more than happy. Over the next seven years Tytler wrote hundreds of articles on science and history, and almost all of the minor articles, although many of those articles had dubious science. For example, in the article on Noah’s Ark, Tytler goes into great length describing the architecture of the Ark, complete with an illustrated copperplate engraving. In another article, Tytler includes a remarkably precise chronology for the Earth, beginning with its creation on 23 October 4004 B.C. and noting that the Great Flood of 2348 B.C. lasted for exactly 777 days.

One of Tytler’s admiring biographer, Robert Burns, estimates that Tytler alone wrote over three-quarters of the second edition. The first edition of Encyclopædia Britannica had three volumes, totaling 2,391 pages. Under the editorship of James Tytler, Britannica became a ten volume encyclopedia with a staggering 8,595 pages, and five times as many long articles as the 1st edition.

James Tytler continued writing for Encyclopædia Britannica even after he was dropped from editorship for the third edition. One of his most infamous contribution was on the subject “Motion”, where Tytler rejected Newton’s theory of gravitation and wrote that gravity is caused by the classical element of fire.

Nonetheless, the years working for Encyclopaedia Britannica were some of the most prosperous in his life, where Tytler enjoyed enough financial freedom to indulge in such activities as ballooning. At that time Britain was swept by balloon mania after the Montgolfier brothers' successful flight at Versailles in 1783. Tytler decided he wanted to fly too.

After several unsuccessful attempts, on 25 August 1784, Tytler soared 350 feet into the air in a balloon over Comely Gardens near King’s Park, becoming the first person in Britain to ascend in a balloon. Later attempts were less fortunate. His last flight crashed into a tree and the coal stove that heated air for the balloon exploded nearly killing him. Tytler didn’t fly anymore, but his efforts did earn him the title of “Balloon Tytler”.

After his brief career as an aeronaut, Tytler devoted himself to literary work again. In 1792 Tytler fell foul with the authorities because of his radical political views and had to escape to America. He took refugee in Salem, Massachusetts, where he spent the remaining years of his life eking out a living through journalism and literary compilations. In January 1804, while returning home after a night of drinking, Tytler fell into a ditch and froze to death.

Leading image of Encyclopædia Britannica volumes by Joi Ito

Comments

Post a Comment