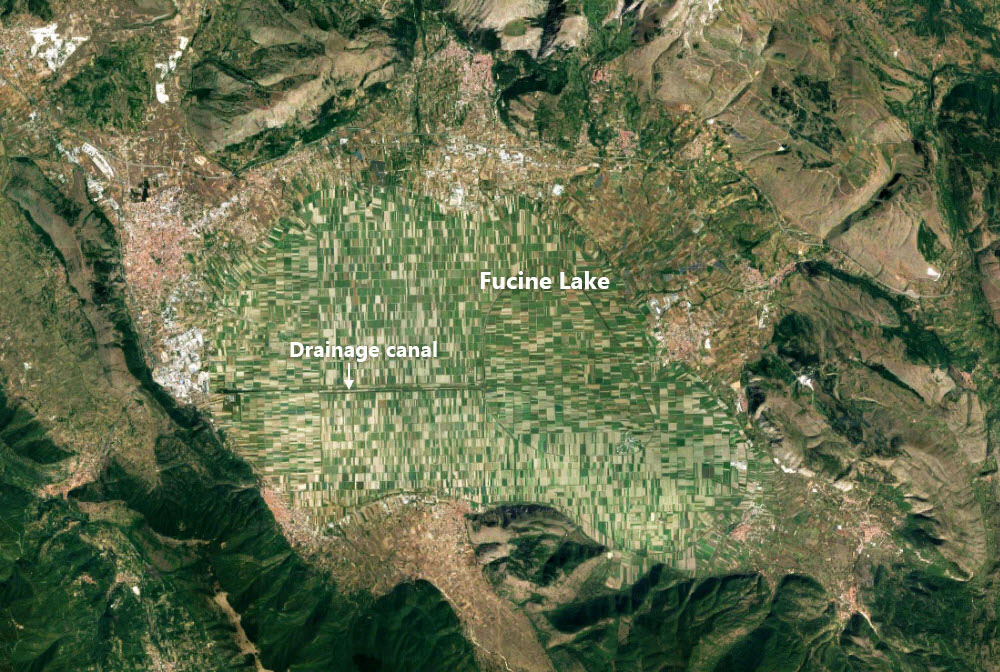

In western Abruzzo, in central Italy, about 80 kilometers east of Rome, lies one of Italy's most fertile plains. The vegetables that are grown here are highly appreciated across Italy for their distinguishing quality and taste. Particularly popular is the Fucino potato which was awarded the “Protected Geographical Indication” in 2014—a quality label awarded by the European Union to agricultural products of excellence closely tied to a particular territory.

Surrounded by low hills, this wide and shallow valley was not always occupied by farmlands. On the contrary, there was a lake here, and it was the third largest lake in Italy until it was drained in 1878.

Fucine Lake, or Lago Fucino in Italian, was the source of misery since ancient times. The lake had no natural outlet, causing the lake’s water to spill over and frequently flood the surrounding villages. The local inhabitants pressed Julius Caesar to drain the lake and reclaim the valley, but before Caesar could draw up a plan, he was assassinated.

A century later, in 41 AD, Emperor Claudius took up the ambitious plan of regulating the flow of the Fucine Lake. To achieve that, Claudius dug a 6-kilometer-long tunnel through the hills near Avezzano to divert the lake waters into the Liri River. Over thirty thousand workers, mostly slaves, toiled for eleven years digging, levelling and tunneling through the hills. Such a grandiose project had never been attempted before. Landslides and collapsed tunnels claimed untold number of lives. The work almost proved to be a disaster when a miscalculation by the engineers caused the lake waters to come rushing out too soon nearly drowning Claudius and his party, who had gathered on a floating platform on the channel.

Eventually, the tunnel was completed. At that time it was the longest tunnel ever built, and remained so for eighteen centuries until the inauguration of the Fréjus Rail Tunnel under the Alps in 1871. To celebrate the completion of the drainage works, Claudius organized a massive naval battle, called naumachia, on Fucine Lake. The combatants were prisoners who had been condemned to death. The spectacle on Fucine Lake was a carnage, as Roman naumachia usually were. After the battle, the locks were opened and the bloody waters of Fucine Lake flowed out, reducing the size of the lake from 140 sq. kilometers to under 60 sq. kilometers.

The tunnel today. Photo: Claudio Parente/Wikimedia Commons

The tunnel today. Photo: Claudio Parente/Wikimedia Commons

After the fall of the Roman Empire and the Barbarian invasions, maintenance of the tunnel failed causing it to clog up. In the early 6th century, there was a serious earthquake that shifted the lake bed relative to the tunnel entrance, and as a consequence the lake returned to its former levels. After several unsuccessful attempts to restore the Roman drainage system in the 13th and the 15th centuries, Italian nobleman and banker Alessandro Torlonia engaged Swiss engineer Jean François Mayor de Montricher with the complicated task.

After more than a decade of work, Montricher was able to restore the original tunnels enlarging sections of it wherever required. Other canals and connecting wells were also added. The work was concluded in 1870, and in 1873 the gradual draining of the Fucine Lake began. In five years, the lake was completely drained leaving behind 140 square kilometers of fertile land. Fucine’s fishermen discarded their fishing nets and took up farming instead, cultivating the former lakebed with cereals, vegetables and sugar beets.

In 1942, a second tunnel or emissary was dug to compensate the functions of the original. These tunnels continue to drain runoff and excess water from the cultivated fields, so that there is a continuous flow of water at roughly 9 cubic meters per second through the emissary.

In 1876, Roman architect Carlo Nicola Carnevali, built a couple of switch gates and a three-arched bridge on the head of the main emissary. A 23-feet-high statue of the Immaculate Conception decorates the structure. The sluice gates regulates the flow of the waters coming from the numerous Fucine canals which then pour into the outer drainage canal. From there, the water flows through the tunnel under Mount Salviano and exits on the opposite side of the hill to merge with the Liri River.

Entrances to the major tunnel. Photo: Claudio Parente/Wikimedia Commons

The outlet of the tunnel. Photo: F.angelo/Wikimedia Commons

References:

# Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tunnels_of_Claudius

# NASA, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/8572/lake-fucine-italy

# http://www.aercalor.altervista.org/index_file/Lago_Fucino.pdf

# Hughes, Robert. Rome: A Cultural, Visual, and Personal History

Comments

Post a Comment