When cotton first came to Europe from Central Asia during the Middle ages, people were fascinated by the fluffy, fibrous balls that resembled wool. They knew cotton grew on trees, but they were unaware exactly how. Having never seen a flower that fluffy, people just assumed that the cotton came from lambs, but the lambs themselves grew on trees.

Sound incredulous? Not quite, considering how little people knew about their surroundings in those times. Even today many people have no idea how different the variety of fruits and vegetables they eat look in their natural state. A couple of months ago, an internet user shared an image of a pineapple plantation on the very popular social media site Reddit. It garnered more than 86 thousand votes and 1,700 comments, most of which were expression of surprise.

“I thought they grew on palm trees,” wrote one user.

“I assumed the green tuft was the stem,” wrote another.

“42 years of life before I saw and knew this,” confessed another.

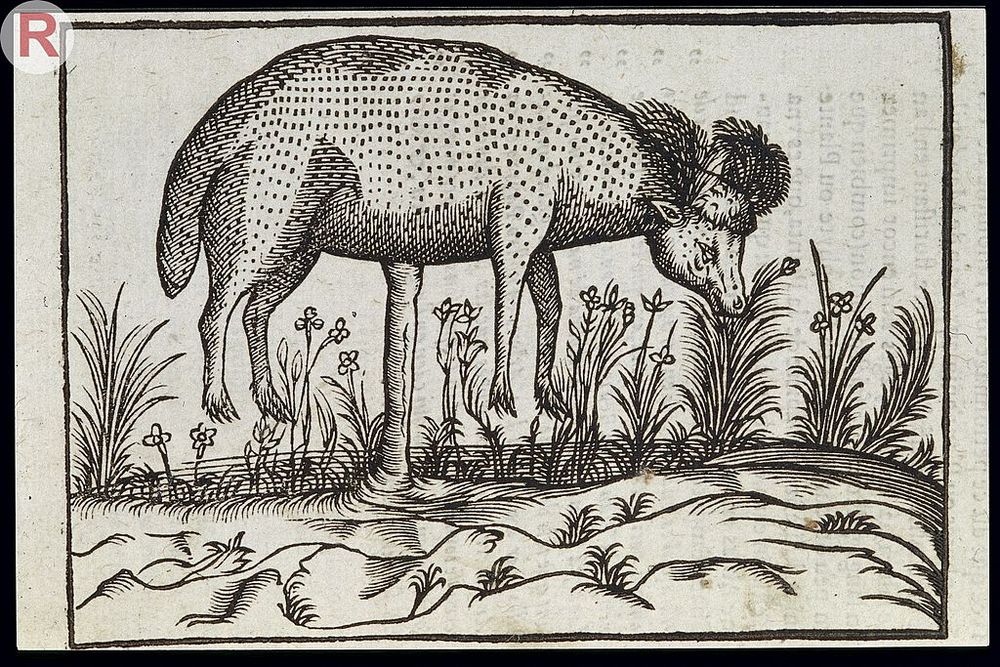

The myth of a lamb-producing tree can be traced all the way back to the 5th century, first mentioned in a Jewish text called Talmud Ierosolimitanum by Rabbi Jochanan. It tells of a plant-animal having the form of a lamb and attached to the ground by a stalk like an umbilical cord. Its delicate flesh, loved both by humans and wolves, were said to taste like fish and blood as sweet as honey.

The myth was furthered through the writings of Sir John Mandeville, a compulsive liar, who made up many of his travel stories and fabulous tales from distant lands. Mandeville placed the source of the plant in Tartary, a historical region around the Caspian Sea and the Ural Mountains.

There were two variations of the vegetable lamb myth. In one, the plant was said to bore many different pods, each of which produced one tiny lamb. In the other, a single lamb was comically set upon the top of the plant swinging hopelessly with the wind. The stalk was flexible, so when the perched lamb became hungry he could bend down to feed on the vegetation surrounding it. Once the food ran out, the lamb died.

Even in those time there were skeptic minds, like the great Italian polymath Girolamo Cardano, who pointed out in 1557 that soil could not provide the requisite heat for the lamb to survive, especially during its embryonic development. Before long botanists began to wonder that maybe there were plants that resembled lambs and were misidentified as thus. The first shred of evidence supporting this theory came from the celebrated physician and botanist, Sir Hans Sloane, who presented to the London’s Royal Society a plant procured from China. The specimen was a foot long, having a body covered with dark, yellowish hair, much like a lamb. The plant, a rhizome called Cibotium barometz, has numerous protruding appendages that can resemble the legs of a woolly lamb. Although it was far from convincing, the scientific community considered the mystery essentially solved. Nearly a century later, a German scholar and physician, Engelbert Kaempfer, went hunting for the mythical plant to Persia and came empty handed. After speaking with native inhabitants and finding no physical evidence of the lamb-plant, Kaempfer concluded it to be nothing but legend.

We know that cotton was originally cultivated in India and was brought from there by the ancient Greeks, who penned very poetic verses extolling the plant. Herodotus wrote that “certain trees bear for their fruit fleeces surpassing those of sheep in beauty and excellence, and the natives clothe themselves in cloths made therefrom.”

Alexander the Great’s admiral reported that “there were in India trees bearing, as it were, flocks or bunches of wool, and that the natives made of this wool garments of surpassing whiteness.” Another of Alexander’s generals mentioned the cotton plant in his journal under the name “wool-bearing tree.”The 19th-century naturalist Henry Lee, who made extensive research on the origin of the vegetable lamb, noticed that the Greek word for melon “μηλον”, often used to describe the form and appearance of the unripe cotton-pod, can also be translated into “fruit,” “apple,” or “sheep”. Lee believes that this ambiguous phrase, misinterpreted throughout various translation, may have contributed to the myth.

In those credulous times, the idea of plants producing animals was not that unreasonable for people with scant education and increasing wonder of the natural world. As an example, it was once believed that the barnacle goose grew on trees found in the British Isles. The goose would drop down from the trees into water, and immediately fly out.

Incidentally, there is a white flower belonging to the genus Raoulia growing in the alpine areas of New Zealand, that grow in such large, compact clusters that from the distance, they appear as grazing sheep, giving the flowers the name “vegetable sheep”.

Vegetable sheep. Photo: Rebecca Bowater/Flickr

References:

# Henry Lee, The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43343/43343-h/43343-h.htm

# Scientific American, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/running-ponies/animal-or-vegetable-legend-of-the-vegetable-lamb-of-tartary/

# Wired, https://www.wired.com/2014/04/fantastically-wrong-vegetable-lamb-tartary/

# Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vegetable_Lamb_of_Tartary

Comments

Post a Comment