On the night of February 9, 1913, inhabitants of a large portion of the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada witnessed a meteoric spectacle that has been described by astronomers as one “without parallel”.

As it was a cloudy winter night, most people were likely indoors and didn’t see anything. But a few lucky individuals with clearer conditions noticed that around 9 PM, a procession of 40 to 60 bright fireballs appeared in the dark sky moving slowly “with peculiar, majestic, dignified deliberation” from one end of the horizon to the other, on a perfectly horizontal path until they disappeared in the distance. The procession was soundless but at least eight stations in Canada picked up rumbling noises accompanied by shaking of buildings. In many other places loud, thunder-like sounds were heard, occasionally by people who had not seen the meteors themselves.

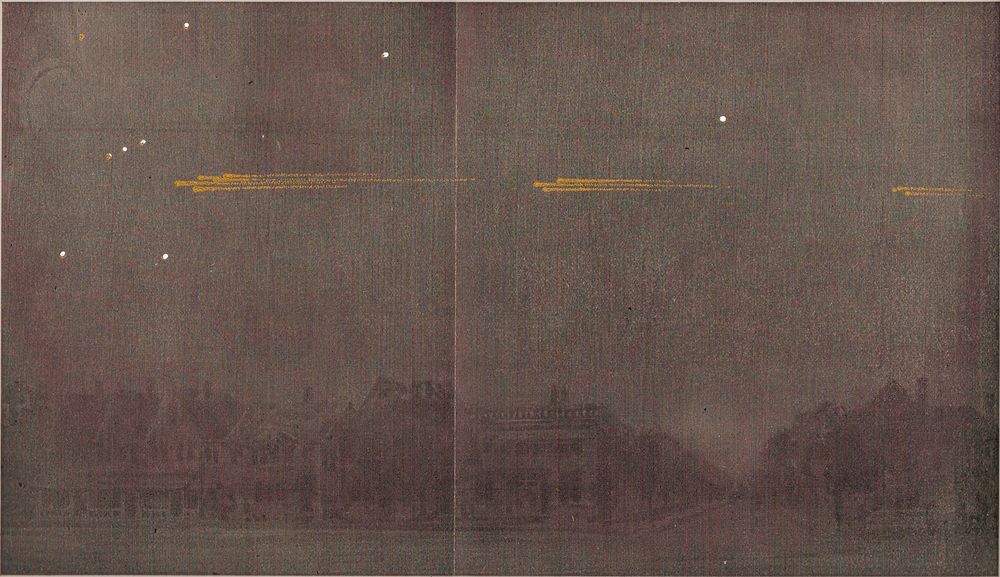

Painting by artist Gustav Hahn who was fortunate enough to witness the event first hand.

Canadian astronomer Clarence Chant, who investigated the phenomenon the same year, noted that unlike most shooting stars that “are visible for but a very short time, and the brilliant ones very generally descend rapidly towards the earth”, these bodies were “moving leisurely along, giving ample time for the fortunate observer to make several wishes if he were so inclined.” Some of the witnesses Chant interviewed reported that “just before disappearing this body burst, leaving behind it a trail of stars.”

Chant continues:

Before the astonishment aroused by this first meteor had subsided, other bodies were seen coming from the north-west, emerging from precisely the same place as the first one, Onward they moved, at the same deliberate pace, in twos or threes or fours, with tails streaming behind, though not so long nor so bright as in the first case. They all traversed the same path and were headed for the same point in the south-eastern sky. Gradually the bodies became smaller, until the last ones were but red sparks, some of which were snuffed out before they reached their destination. Several report that near the middle of the great procession was a fine large star without a tail, and that a similar body brought up the rear.

The most outstanding feature of the phenomenon “was the slow, majestic motion of the bodies; and almost equally remarkable was the perfect formation which they retained”. Some witnesses compared the spectacle to a fleet of airships, or battleships attended by cruisers and destroyers. Others thought they resembled a brilliantly lighted passenger train.

Most naked-eye observers Chant spoke to reported varying number of meteor bodies. Some observers reported a dozen or fewer objects, while others claimed to have seen hundreds or even thousands. Only one witness, a pupil of the Trenton High School, reportedly viewed the meteors with any kind of instrument, a opera glass in this case. According to him there were about ten groups in all and each group consisted between twenty to forty meteors.

The entire procession took about 3.3 minutes to traverse the sky. Chant notes that “this is an extraordinarily long time... but there is good evidence that it is not an exaggeration.”

The meteor train was also visible over an unprecedented distance. Initially, Chant calculated a meteor procession stretching over more than 2,500 miles of the Earth’s surface, but according to leading astronomer William Frederick Denning (1848—1931), the height of the meteors should be somewhat higher than Chant determined, nearer to 38 miles than 26 miles, which would translate to an even longer flight path. Denning wondered whether there were sailors in the Atlantic Ocean who might have witnessed the same spectacle. His call for observation returned at least two witnesses, one of which reported seeing the meteors off the coast of Brazil, some 5,500 miles from the first sighting. A 2013 study by Don Olson of Texas State University and Steve Hutcheon of the Astronomical Association of Queensland, Australia, extending the known path of the procession by an additional thousand miles—an extraordinary distance for meteors to follow the curvature of the planet without plunging to earth or skipping back into space.

The trajectory of the meteor procession. The red dots mark observed locations of the Great Meteor Procession of 1913. Image credit: Don Olson

Another great mystery is the appearance of several other bright meteors within a few hours of the great display, including another meteor procession on the same course around 5 hours later, although the Earth's rotation meant that there was no obvious mechanism to explain this. One observer, an A. W. Brown from Thamesville, Ontario, reported seeing both the initial meteor procession and a second one on the same course at 02:20 the next morning. Reports of meteor observations continued until the next day. The Toronto Daily Star for February 10 reported a curious observation:

At about 2pm on that date some of the occupants of a tall building near the lake front saw some strange objects moving out over the lake and passing to the east. They were not seen clearly enough to determine their nature, but they did not seem to be clouds, or birds, or smoke, and it was suggested at the time that, perhaps, they were airships cruising over the city. Afterwards, it was surmised that they may have been of the nature of meteors moving in much the same path as those seen the night before.

Yet another peculiarity of the meteor procession of 1913 was the absence of a radiant, that is, there was no point in the sky from which the meteors appeared to originate. For instance, the annual meteor Perseids, which peak each August, get their name because they appear to come from an area in the constellation Perseus, called the radiant. In the case of the meteor procession of 1913, this radiant was absent. The meteors did not spread in all directions from a point, but followed closely similar paths across the sky.

Charles Fort, an early-20th-century chronicler of the unexplained, suggested in his 1923 book New Lands that the procession might have been the work of an extraterrestrial intelligence rather than a rogue space rock. Fort cites descriptions of first-hand observers as reported by Chant, many of which compared them “to a fleet of airships, with lights on either side and forward and aft”. Others, likened them to “great battleships attended by cruisers and destroyers”. Still others thought they “resembled a brilliantly lighted passenger train, traveling in sections and seen from a distance of several miles.”

The current hypothesis is that a wandering space rock (or a number of bodies) was captured by the earth’s gravitational pull and put into a temporary orbit which then disintegrated shortly. The phenomenon of 1913 was repeated, in parts, on August 10, 1972 when a meteor penetrated the atmosphere over Utah, descended to a height of about 36 miles (58 km), and later escaped the atmosphere over Alberta, Canada, flying off into space. While travelling through the atmosphere it produced a bright daylight fireball. However, the flight of the 1972 fireball did not involve a procession of meteoric objects, and its trajectory was also much shorter at some 940 miles.

Meteor procession itself is a rare occurrence with only a handful of examples in history, the most famous being the Great Meteor of 1783, which we discussed earlier. The meteor procession of 1860 is another one, and is believed to have inspired Walt Whitman to write the poem Year of Meteors, 1859-60. Another procession was observed in 1876.

References:

# Clarence Chant, An Extraordinary Meteoric Display

# Horace A. Smith, The Great Meteor Procession Of February 9, 1913, PDF

# Patrick Metzger, Was the Great Meteor Procession of 1913 More Than Met the Eye?, The Torontoist

Comments

Post a Comment