The Witchcraft Act of 1735 was a landmark act for Britain. Unlike the earlier Witchcraft Acts which legalized witch-hunting and the execution of witches, the 1735 act was a complete reversal of attitudes. It ruled that witches didn’t exist and it was a crime for a person to accuse another of possessing magical powers or practicing witchcraft. Furthermore, anybody who pretended to exercise witchcraft, sorcery, or conjuration, by claiming to call up spirits, foretell the future, or cast spells, was to be punished as a con artist and subject to fines and imprisonment. The criminalization of witchcraft brought to an end the gruesome practice of burning innocent victims on the stake, that had claimed the lives of tens of thousands of women since medieval times.

Helen Duncan

The Witchcraft Act 1735 remained in forced for more than two hundred years, during which it was frequently invoked, particularly during the early 19th century by the political elite to root out “ignorance, superstition, criminality and insurrection” among the general populace. Before its eventual repeal by the Fraudulent Mediums Act of 1951, it was invoked one last time in 1944 to prosecute a forty-seven year old Scottish woman named Helen Duncan. Her conviction and sentencing earned her the title of “the last witch of Britain.”

Helen Duncan (born Helen MacFarlane) was born in Callander, Scotland, in 1897. Even as a child, Helen was quite the imposter. She claimed clairvoyance and drove her fellow pupils at school to terror by predicting doom and destruction for all sorts of people, much to the distress of her mother, who was a devout member of the Presbyterian church. At the age of 18, she married Henry Duncan, a wounded war veteran, and together the pair went on to have six children. Struggling to provide for her large family, Helen, encouraged by her husband, began holding seances and recalling spirits. Pretty soon she was travelling across Britain hosting seances and bringing comfort to grieving families who could speak to their dead loved ones in the spirit world.

One of her tricks was to produce a slimy, otherworldly substance known as ectoplasm from her mouth and nose, which would then transform into physical beings of the spirits being recalled, and then communicate with their loved ones. Helen managed to fool many learned men with her antics, even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, who was known for his great gift of logical deductions.

Vincent Woodcock was one man who claimed Helen Duncan changed his life. Giving evidence at the Old Bailey during Duncan’s trial in 1944, Woodcock claimed that his dead wife appeared in 19 séances he had attended over a period of three years. On one occasion, he had brought his sister-in-law when Duncan went into a trance and began producing ectoplasm from her mouth. The deceased wife then materialized from the ectoplasm and asked Woodcock and his sister-in-law to come forward. The spirit then removed the wedding ring from her husband’s finger and put it on the palm of her sister, adding “It is my wish that this takes place for the sake of our little girl.” A year later, the couple were married and returned for another séance during which the dead woman appeared once more to give her blessings to the happy couple.

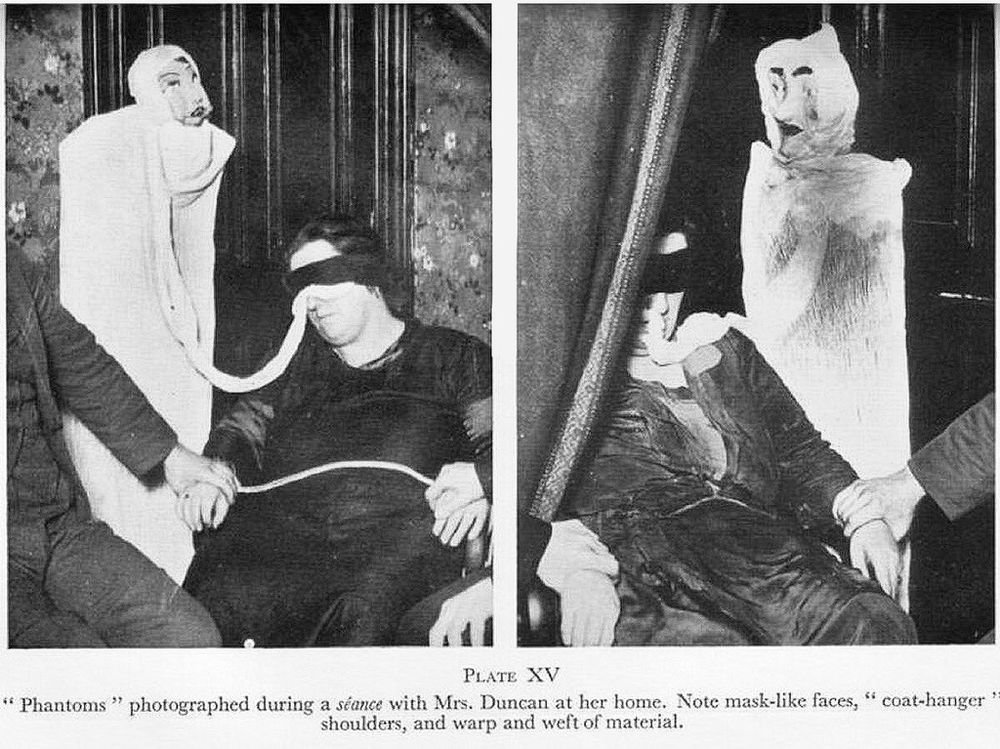

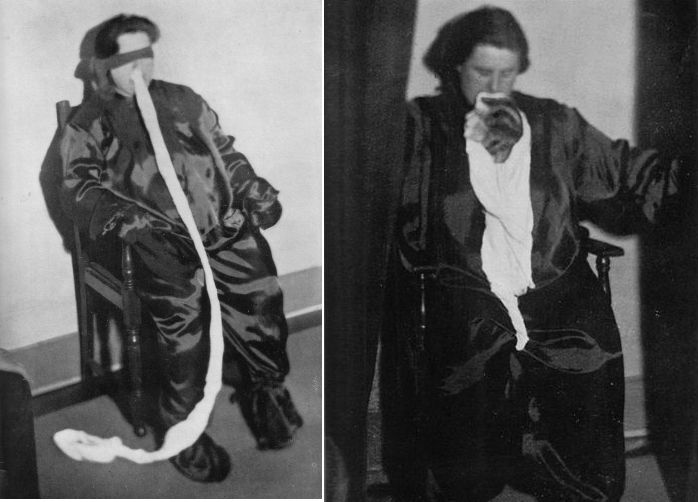

But not everyone shared her devotees’ faith in her supernatural powers. In 1928, photographer Harvey Metcalfe attended one of Duncan’s séances and took flash photographs of her alleged spirits. The photographs revealed that the spirits were nothing more than dolls made from a painted papier-mâché mask draped in an old sheet. Three years later, the London Spiritualist Alliance investigated Duncan and concluded that the ectoplasm was made of cheesecloth and paper, mixed with egg whites. The Alliance also determined that Duncan swallowed the supposed ‘ectoplasm’ sometime before her performance and regurgitated the same during her séance. When the committee forced her to swallow a dye before one of her séances, Duncan produced no ectoplasm.

Photographs shot by Harvey Metcalfe during a 1928 séance exposed Duncan’s fraud.

Helen Duncan expelling cheesecloth ectoplasm.

Attempts to X-ray her turned difficult, as she ran away from the laboratory after smacking the face of her husband and making a scene on the street. According to psychical researcher Harry Price, “Mrs. Duncan, without the slightest warning, dashed out into the street, had an attack of hysteria and began to tear her séance garment to pieces. She clutched the railings and screamed and screamed.” After pacifying the woman, Duncan returned to the laboratory and demanded to be X-rayed—an insistence Price attributed to her having already passed the ingested ectoplasm cheesecloth to her husband during the chaos on the street. When the doctor asked Henry Duncan to turn out his pockets, he refused.

Duncan was finally caught in the act during a performance in Edinburgh in 1933. During the séance, the spirit of a little girl called Peggy emerged. A member of the audience lunged at the emerging shape and the lights were turned on. The spirit was revealed to be made from a stockinette undervest. Duncan was charged with fraud and fined £10.

But Duncan’s career was far from over. She continued to practice her spiritualist activities, and came into great demand during World War 2 from families of those lost in active service. In 1941, at one of her seances in Portsmouth, headquarters of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet, a deceased sailor allegedly materialized. The spirit of the sailor revealed that a British battleship HMS Barham had sunk with more than 800 lives on board, when the ship was torpedoed by a German U-Boat. The news came as a shock to those present because no announcement of such a tragedy had been made by the War Office. Yet, the information turned out to be true: HMS Barham had indeed sunk a few days earlier, but the news was kept from the public and only revealed to the relatives of the casualties in strict confidence. With more than eight hundred affected families and several members in every family, the news was hardly a closely guarded secret. Duncan apparently got wind of the tragedy and decided to use it to her advantage.

A piece of “ectoplasm”—this one made of artificial silk—at the Cambridge University Library.

But the Navy wasn’t going to take chances. What if Duncan was really clairvoyant? What if she revealed classified military information to the enemy? With the critical D-Day landings on the horizon, the British government ordered Duncan’s arrest. On 19 January 1944, a couple of undercover policemen went to a séance taking place in Portsmouth. When a white-shrouded manifestation appeared, the policemen pounced on the figure, and it was found to be Duncan herself in a white cloth.

Duncan was arrested and initially charged under the Vagrancy Act of 1824, which was a minor offense. But the authorities considered her crime serious and eventually discovered section 4 of the Witchcraft Act which covered fraudulent spiritual activity and carried the heavier penalty of a prison sentence. The subsequent trial was a media sensation. Many witnesses were called in to the stand and some recalled their experiences defending Duncan. But the jury was not moved: they returned the guilty verdict, and the judged sentenced her to 9 months.

Upon her release, Duncan went back to seances despite promising the court never to hold one, and was arrested again in 1956. She died a short time later in her home in Edinburgh.

Duncan’s trial most certainly contributed to the repeal of the Witchcraft Act. Winston Churchill was furious when he learnt that an archaic act was used in a modern court of law. He dashed a letter to Herbert Morrison at the Home Office, where he wrote: “Let me have a report on why the Witchcraft Act, 1735, was used in a modern Court of Justice… What was the cost of this trial to the State, observing that witnesses were brought from Portsmouth and maintained here in this crowded London, for a fortnight, and the Recorder kept busy with all this obsolete tomfoolery, to the detriment of necessary work in the Courts?”

In 1951, the Witchcraft Act 1735 was repealed with the enactment of the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951, largely at the instigation of Spiritualists through the agency of Thomas Brooks, a Labour Party MP.

On several occasions, descendants and supporters of Duncan have campaigned to have her posthumously pardoned of witchcraft charges, but time and again, the Scottish Parliament have rejected these petitions.

References:

# Conjuring up the dead: Helen Duncan and her ectoplasm spirits, History Extra

# The truth about the UK's last witch Helen Duncan, The National

Comments

Post a Comment