For the past five hundred years, the people of Rome have voiced their resentment against the authorities through a unique medium—short compositions and satirical verses ridiculing the government, the pope and his behavior. These humorous expressions of political discontent were posted anonymously on various prominent statues around the city where people met and discussed matters relating to their personal lives as well as the state. The prominence of the statues gave these anonymous voices exposure, and the discussion often veered towards the subject matter raised. Eventually, the people began to use these statues to talk back and forth, the same way people use bulletin boards today. These statues came to be known as the “talking statues of Rome” or the Congregation of Wits.

The Statue of Pasquin in the House of Cardinal Ursino, by Nicolas Beatrizet (1515–1565)

One of the first popes whose action attracted harsh criticism was Pope Nicholas V (1447-55). Nicholas wasn’t exactly a bad pope. A key figure in the Roman Renaissance, Nicholas was instrumental in making Rome the home of literature and art. He strengthened fortifications, restored aqueducts, and rebuilt many churches. He ordered design plans for what would eventually be the Basilica of St. Peter. He also played an important role in establishing the Vatican library and saved thousands of manuscripts he rescued from the Turks after the fall of Constantinople.

The Roman populace, however, couldn’t appreciate his work, and conspired to overthrow the papal government. When Nicholas discovered the plot, he arrested the conspirators and had them hanged. Nicholas’s heavy-handed justice was criticized in a short poem:

Da quando è Niccolò papa e assassino, abbonda a Roma il sangue e scarso è il vino.

(Since Nicholas became pope and murderer,

Blood is abundant in Rome while there is lack of wine.)

Of the six talking statues in Rome, the most famous is a battered Hellenistic-style statue dating to the third century BC called Pasquino. The statue was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome in the fifteenth century and erected in a corner of the Palazzo Braschi. Each year on St. Mark’s Day the Cardinal organized a sort of Latin literary competition and poems were posted on the statue, but occasionally some continued to post poems outside the competition period. In this way Pasquino became the first talking statue of Rome.

Pasquino. Photo credit: Yahti.com/Flickr

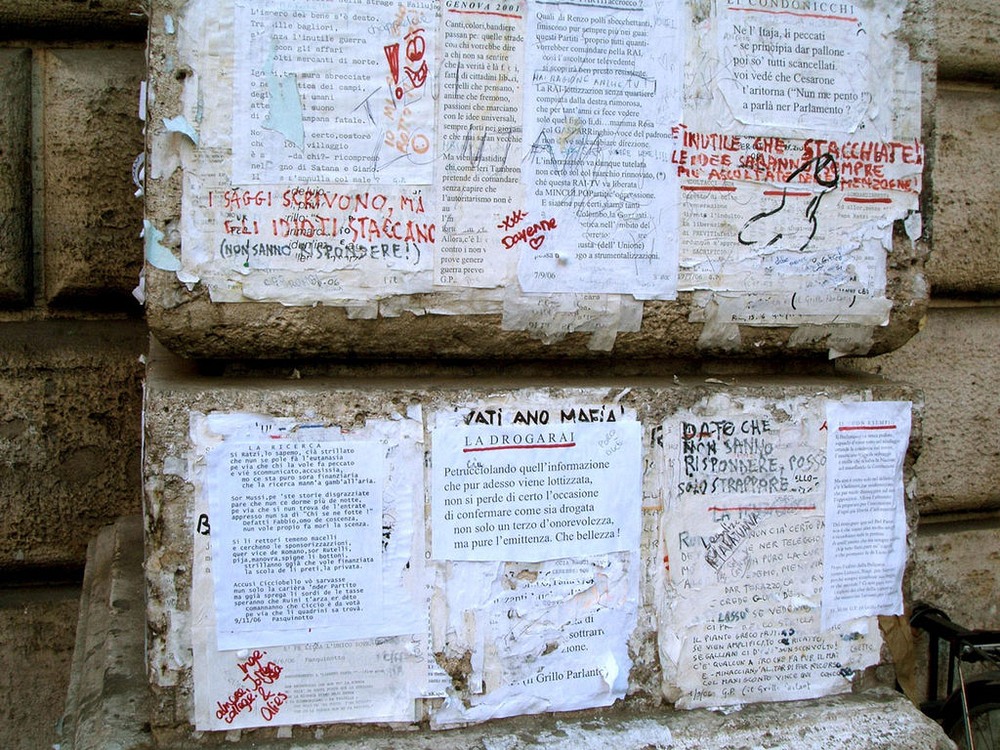

Photo credit: Pippo-b/Wikimedia

Messages were normally posted at night under the cover of darkness, so when people gathered around the statue the next morning they could read the notes and have a good laugh before the messages were removed by the authorities. In order to put an end to the practice, Pope Adrian VI (1522-23) threatened to have Pasquino thrown into the Tiber, but changed his mind fearing ridicule for punishing a statue. Instead, strict laws were enforced and Pasquino was placed under surveillance. This had the unintended consequence of people turning to other statues. The colossal statue of a river-god at the foot of the Capitol Hill, named Marforio, soon became the second talking statue.

To add zest to the lampooning of the popes, both statues began to talk to each other. Marforio once asked: “Pasquino, why has oil got so expensive?”, to which Pasquino replied: “Because Napoleon needs it to fry republics and anoint kings.”

Another time, the statues mocked Camilla, the sister of Pope Sixtus V, who came from peasant origins but began to assume the attitude of a noblewomen. To Marforio’s question: “Hey, Pasquino, why is your shirt so dirty? You look like a coal merchant!” Pasquino replied, “What can I do? My washerwoman has been made a princess!”

One of the most famous satires was centered around Pope Urban VIII Barberini (1623–44), who had the bronze from the Pantheon melted down to use in St. Peter’s Basilica. Criticizing his actions somebody wrote:

“Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini”

(What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did.)

In 1679, on the pretext of preserving the fine antique statue, Marforio was placed in the courtyard of the Palazzo Nuovo, where it remains today.

Marforio, carved in the 1st century, depicts a reclining bearded river god or Oceanus, which in the past has been variously identified as a depiction of Jupiter, Neptune, or the Tiber. Photo credit: Jose Luiz/Wikimedia

Pasquino is still used to this day for posting messages poking fun at the authorities. In 2011, in response to the sex scandals around then Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, messages began to appear on small post-it notes. “Italy is not a brothel”, one read, and “The body of Italy is not for sale,” read another. When Pasquino was wrapped up during restoration, a note appeared: “You can wrap Pasquino well but he will never shut up.”

“Pasquinade” is an actual word today, used not only in Italy but throughout the world. The Oxford Dictionary describes it as “a satire or lampoon, originally one displayed or delivered in a public place.”

Fontana del Babuino is a statue of depicting a Silenus, a deity that was half man and half satyr. The people of Rome called the figure “babuino” because they considered it ugly and deformed, like a monkey. Photo credit: Son of Groucho/Wikimedia

The Fontana del Facchino, or “The Porter Fountain”, was sculpted towards the end of the sixteenth century and depicts a man who sold water from the public fountains from door to door. Photo credit: Lalupa/Wikimedia

One of the six talking statues, the bust of Madama Lucrezia is enormous. It stands 3 meters tall, sited on a plinth in the corner of a piazza between the Palazzo Venezia and the basilica of St. Mark. The statue is badly disfigured, but it probably represents the Egyptian goddess Isis. The nickname is a reference to a noble lady of the 15th century, Lucrezia d’Alagna, who was the mistress of the king of Naples, Alfonso of Aragon. Photo credit: Lalupa/Wikimedia

This headless statue of a man holding a scroll, probably a Roman magistrate or orator, from the late imperial era, was nicknamed Abbot Luigi because of its resemblance to a clergyman from the nearby chiesa del Sudario. It is the last talking statue of Rome. An inscription on its plinth testifies to Abate Luigi's loquacity:

I was a citizen of Ancient Rome

Now all call me Abbot Louis

Along with Marforio and Pasquino I conquer

Eternal fame for Urban Satire

I received offences, disgrace, and burial,

till here I found new life and finally safety

Comments

Post a Comment