About 12 kilometers southwest of the ancient city of Ecbatana (modern Hamadan) in western Iran, and 2,000 meters above sea level on Mount Alvand, are two huge panels carved into the rock. They are cuneiform inscriptions made in the time of Darius I the Great and his son Xerxes I.

At some point in antiquity, possibly after Alexander's conquest, the inscriptions became unreadable as there was no longer anyone who knew how to read the ancient cuneiform script.

Local people began to make legends and conjectures about them, and came to the conclusion that they must contain the secret code that leads to a fabulous hidden treasure, so they called the place Ganj Nameh, literally book of treasures.

The Ganj Nameh Inscriptions. Photo: Salman arab ameri/Wikimedia

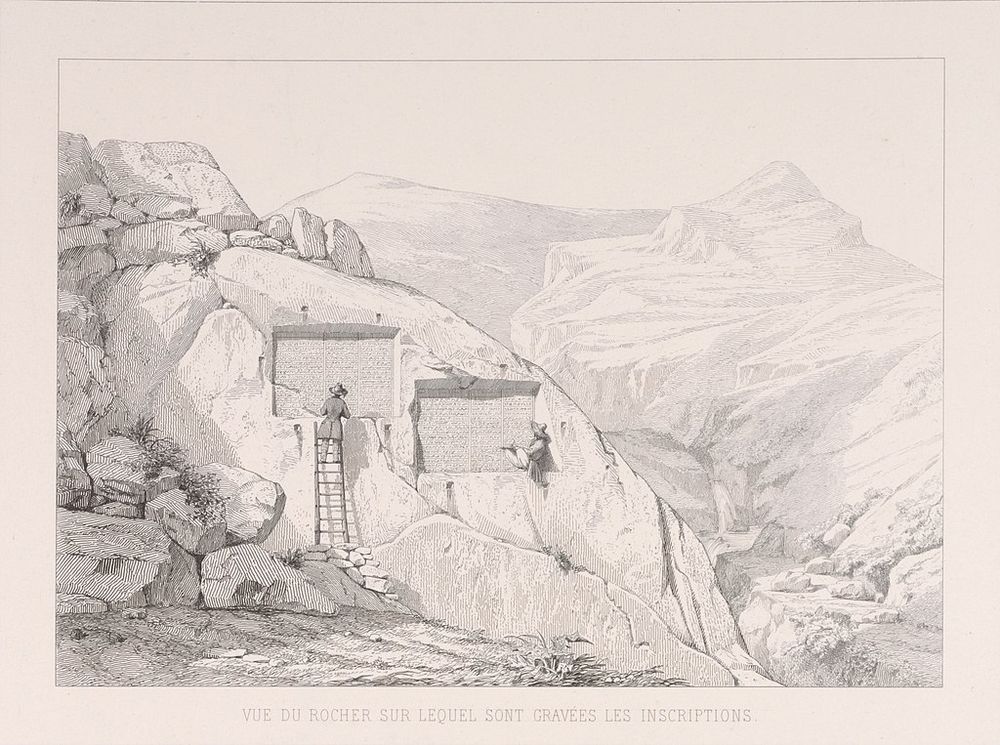

On his 1839 trip to Iran commissioned by the Institut de France, the painter and archaeologist Eugène Flandin made drawings of the inscriptions, which Henry Rawlinson, the father of Assyriology, was later able to decipher. According to Rawlinson, the inscriptions were created on the occasion of one of the trips that both Darius and Xerxes made annually between Ecbatana, the summer residence of the Persian kings and capital of the kingdom of Media, and Babylon.

Ganj Nameh was thus on the northern branch of the royal road built by Darius, which led to Mesopotamia and ended in Sardes, already in Anatolia, after crossing the entire empire.

The inscriptions are carved on a granite rock, just above a stream, and measure 3 meters wide by 2 meters high. They are flanked by holes, which probably served to secure some kind of protective cover. There is also a terrace carved into the rock above the inscriptions.

Drawing by Eugène Flandin showing the inscriptions in 1839. Photo: Wikimedia

The one on the left was made by Darius I the Great (549-486 BC) and the one on the right by Xerxes I (519-465 BC). Both are trilingual as was usual for Achaemenid inscriptions since Darius I. The left block of the inscriptions, 20 lines long, is written in Old Persian, then there is a Neo-Elamite block in the center, and the Neo-Babylonian version on the right.

Old Persian cuneiform is the most recent of the three writing systems, requiring only 34 characters. It was a script of letters that read from left to right and used the wedges tilted to the left as word separators.

By contrast, Elamite and Babylonian required 200 and 600 characters respectively, since they were syllabic scripts.

The inscription of Darius, on the left, and that of Xerxes, on the right. Photo: Adam Jones/Wikimedia

Darius's inscription reads:

The great God is Ahura Mazda, who created this earth, who created that heaven, who created man, who created joy for man, who made Darius king, king among kings, ruler among rulers. I am Darius the Great King, King of kings, King of the lands of many nations, King of this great faraway land too, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid

Xerxes says:

The great God is Ahura Mazda, the greatest of the gods, who created this earth, who created that heaven, who created man, who created joy for man, who made Xerxes king, king among kings, ruler among the rulers. I am Xerxes, the great king, king of kings, king of the lands of many nations, king of this great faraway land too, son of Darius, an Achaemenid

As can be seen, both use the same formulas established during the reign of Darius I the Great, which will be repeated in many other inscriptions throughout the Persian empire. The only difference between the two is the additional predicate on Ahura Mazda, the god of the Zoroastrian religion, who appears in the Xerxes inscription: the greatest of the gods .

Since 1995, the English and modern Persian translations can be read engraved on two granite rocks, very close to the original inscriptions.

Photo: Behzad Alipur/Wikimedia

This article was originally published in La Brújula Verde. It has been translated from Spanish and republished with permission.

Comments

Post a Comment