Twenty years ago, the world's first Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) of 1996, that prohibits nations from conducting any kind of nuclear tests, either for civilian or for military purposes, was approved by the United Nations. At that time, more than two-thirds of the General Assembly's members supported it. That number has now grown to 183. Although the support was strong, some doubted whether the treaty could actually be enforced. After all, what prevents a nation from signing the treaty and then secretly conducting underground nuclear tests?

Licorne nuclear test – French Polynesia, 1970

To prevent nations from violating the treaty, the United Nations decided —shortly after the treaty was approved—to embark on an ambitious engineering feat of creating a global network of sensors that could detect illegal nuclear tests. This global surveillance network is known as the International Monitoring System, and comprises of 337 monitoring facilities spread across the world that uses a variety of methods to detect evidence of nuclear testing. These include seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound and radionuclide detecting stations. These are some of the most sensitive instruments on the planet. Over the years they have recorded not only nuclear tests but earthquakes, rocket launches, supersonic airplanes breaking the sound barrier, the songs of whales, meteors entering and exploding in the atmosphere, the sounds of icebergs breaking and much more. Like a giant sniffer dog, the International Monitoring System looks, listens, feels and sniffs for irregularities on the planet.

Negotiations for nuclear disarmament began as early as 1963 with the signing of the Partial Test-Ban Treaty (PTBT), which prohibited all nuclear tests in the atmosphere and water, out of concern of radioactive fallout, but left out those conducted underground. Neither the United States nor the Soviet Union was willing to adopt a comprehensive test ban that will put an end to all nuclear tests, including those underground, out of fear that either nation will find ways to circumvent any test ban and secretly leap ahead in the nuclear arms race. The United States worried that the Soviet Union would try to covertly conduct underground tests during a test ban, which were more difficult to detect than above-ground tests. Without a system for detecting illicit tests, a comprehensive test ban on nuclear weapons eluded the world for nearly four decades.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the international community got together once again and started to negotiate for a comprehensive ban on nuclear tests. The success of the negotiation depended, in no small part, on the development of a system that could monitor the earth, water and the air for possibly policy violations.

The United Nations created an international body, formally known as the Preparatory Commission for the CTBTO, and tasked it to develop a “verification regime" consisting of instruments, personnel and protocols to detect, verify and report potential evidence of nuclear tests to member states.

Twenty years later, the International Monitoring System is 85 percent done. When completed, it will have 337 stations including: 50 primary and 120 auxiliary seismic monitoring stations to detect seismic waves generated by underground nuclear tests; 11 hydroacoustic stations to detect acoustic waves in the oceans; 60 infrasound stations to detect very low-frequency sound waves in the atmosphere; 80 radionuclide stations to detect radioactive particles released from atmospheric explosions; and 16 radionuclide laboratories for analysis of samples from the radionuclide stations.

Data from all the stations are transmitted to the CTBTO International Data Centre (IDC) in Vienna via a satellite link. With more than half of the planned IMS stations transmitting, the data center receives 10 to 15 gigabytes of data every day, which are then analyzed by the staff.

In 2006, CTBTO’s sensors picked up signs of an underground nuclear test conducted by North Korea. The totalitarian state conducted two more tests in 2009 and 2013, all of which were detected by CTBTO.

The meteor that streaked across the sky over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013 was the largest event picked up to date by the IMS's infrasound network. Photo credit: Alex Alishevskikh/Flickr

But shockwaves of nuclear detonations aren’t the only signals these highly sensitive detectors have been picking up. On February 15, 2013, the CTBTO's infrasound monitoring stations detected signals made by a meteor that disintegrated in the skies over Chelyabinsk, Russia. The data recorded by the sensors helped scientists to locate the meteor, measure the energy release, its altitude and size. Similarly, when Fukushima nuclear power plant blew up in 2011, the infrasound stations detected the explosion and later, the atmospheric sampling sensors were able to monitor the spread of radioactive particles around the globe. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake off Japan's coast was detected by the seismic stations and the ensuing tsunami was well predicted based on data from the hydroacoustic stations.

The International Monitoring System’s extremely sensitive ears have found many uses in a variety of civil and scientific areas such as tsunami warning and weather forecasting, storm tracking, studying of volcanoes, monitoring drifting icebergs in shipping lanes, following migratory habits of birds, the effects of climate change on marine life and many more.

Although the surveillance system has been working for years now, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty is still not in force, which means that the international community cannot legally impose sanctions or penalties on any nation that break compliance. For the treaty to enter into force all 44 countries, the so-called "Annex 2 States" that possess some form of nuclear technology, not necessarily weapons, (for example, nuclear power reactors) has to ratify it. Of those, eight have not: China, Egypt, Iran, Israel and the United States have signed but not ratified it, whereas India, North Korea and Pakistan have done neither.

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty is currently stalled but the surveillance system it created continues to be used in ways its creators never envisioned.

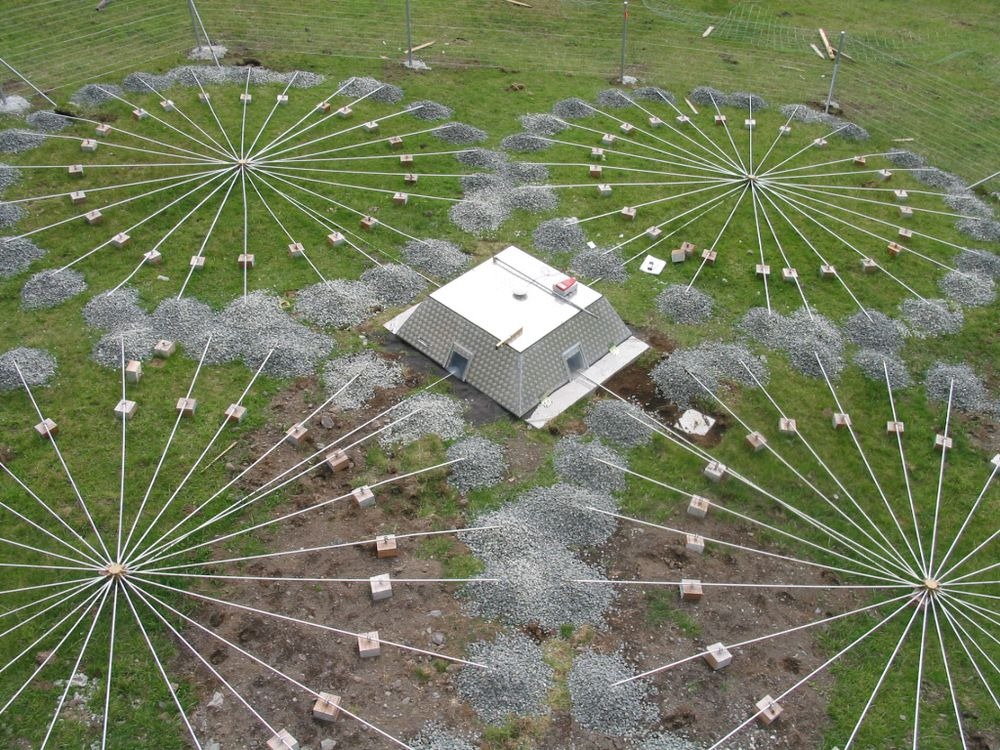

View of infrasound station array at infrasound station IS49, Tristan da Cunha, U.K. Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

Infrasound array at infrasound station IS39, Palau. Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

Primary seismic station PS21, Tehran, Iran. Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

Array at infrasound station IS50, Ascension, U.K. Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

Performing maintenance at infrasound station IS55, Windless Bight, Antarctica (USA). Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

An expert examines radionuclide station RN20 in Beijing, China. Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

Radionuclide Station RN68 Tristan de Cunha, UK. Photo credit: CTBTO Preparatory Commission

Sources: Wikipedia / CTBTO / Earth Magazine / Phys.org / WNYC

Comments

Post a Comment