In the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, there is a bronze aquamanile, or water jug, dating from the late 14th or early 15th century. The aquamanile depicts a woman riding an older man, with the old man on all his fours and the woman sitting on his back. With her right hand, she is grabbing a lock of hair on the old man’s head. The woman in the sculpture is identified as Phyllis, and the old man is none other than the great Greek philosopher Aristotle. But how did Aristotle, one of the greatest thinkers of Classical antiquity, end up dominated and ridden like a horse?

An aquamanile in the form of Aristotle and Phyllis. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

According to this little-known tale, one of Aristotle’s favorite pupil, Alexander the Great, was smitten by a beautiful young woman named Phyllis. Aristotle, concerned that Alexander’s love for Phyllis was distracting him from his kingly duties, cautioned him and advised him to spend less time with the woman. In some versions of the story, Phyllis is the mistress of Alexander’s father, while in others she is Alexander’s lover.

Phyllis was hurt when Alexander began to shun her and became upset at Aristotle when she heard that it was the old man who had encouraged Alexander to do so. To exact revenge, Phyllis started flirting with Aristotle beguiling the old philosopher with her beauty. At last, unable to suppress his carnal desire, Aristotle begged Phyllis to spend a night together, to which Phyllis responded, “Certainly, but on one condition.”.

Phyllis demanded that Aristotle put on a saddle and bridle, and carry her around the garden like a horse. Meanwhile, Phyllis secretly told Alexander to be on a lookout over the garden. When Alexander saw his dignified old tutor crawling over the palace grounds with a bit in his mouth and Phyllis on his back brandishing a whip, he was shocked. He confronted his teacher, who sheepishly excused himself saying: “If thus it happened to me, an old man most wise, that I was deceived by a woman, you can see that I taught you well, that it could happen to you, a young man.”

Aristotle and Phyllis, circa 1485. Image credit: Wikimedia

The story of Phyllis and Aristotle was immensely popular in the middle ages. Scenes from the story, especially the humiliating domination of Aristotle, was painted, carved and chiseled on all manner of objects, from church benches to marble columns to ivory boxes. This cautionary tale is an example of the ‘Power of Women’ trope, where wise and powerful men were depicted vanquished by women. Similar tales ridiculing learned men and depicting female figures being victorious over their male counterparts are found endlessly in medieval iconography and literature. In one example, the Roman poet Virgil became enamored of a beautiful woman called Lucretia, sometimes described as the emperor's daughter or mistress. She played him along and agreed to an rendezvous at her house. Virgil sneaked into at night and climbed into a large wicker basket that Lucretia lowered from a window so he could be lifted up to her room. But she hoisted the basket just halfway up the wall, leaving Virgil trapped and exposed to public mockery the following morning.

These stories became wildly popular in the 15th and 16th centuries when many women were rising in power across Europe. The ability of influential women to overturn accepted social and cultural norms caused dread and concern among citizens. Such concerns in turn may have reinforced anxieties about witchcraft, whose belief was prevalent across Europe.

Phyllis and Aristotle, circa 1500. Image credit: Wikimedia

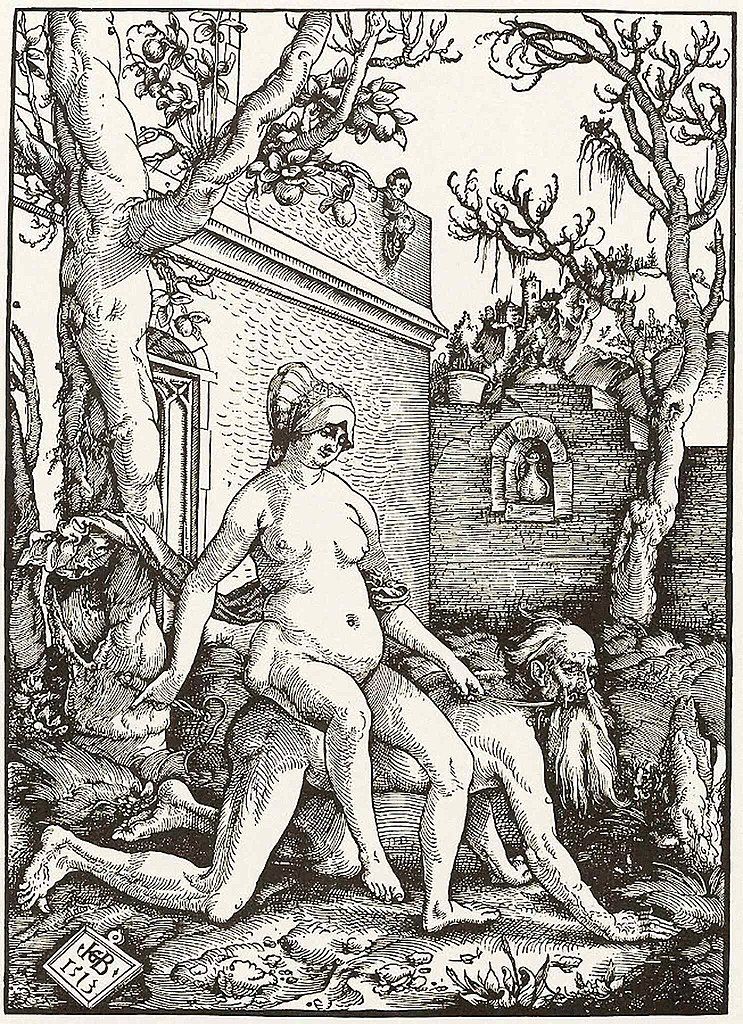

Aristotle and Phyllis, circa 1515. Image credit: Wikimedia

Phyllis and Aristotle, circa 1530. Image credit: Wikimedia

Amelia Soth weighs in about the Phyllis and Aristotle topos:

The “Power of Women” trope was a reflection of the fears and anxieties of a contradictory time. It was an era in which the belief that women were inherently inferior collided with the reality of female rulers, such as Queen Elizabeth, Mary Tudor, Mary, Queen of Scots, Queen Catherine of Portugal, and the archduchesses of the Netherlands, dominating the European scene. To many, the idea of a woman in power seemed unnatural, a reflection of a topsy-turvy universe. [...] Yet the image remains ambiguous. Its popularity cannot be explained simply by misogyny and distrust of female power, because in its inclusion on love-tokens and in bawdy songs there is an element of delight in the unexpected reversal, the transformation of sage into beast of burden.

The story of Phyllis and Aristotle is an edifying tale, but did it really happen? Of course not. The story was a medieval invention and has no connection to the historical Aristotle. It was circulated by a 13th century cleric named Jacques de Vitry, and in the following centuries, the imagery appeared countless number of times in many variations and in diverse places.

“We can easily explain the enduring relevance of the Phyllis on Aristotle motif as just the perennial male anxiety about powerful women,” writes Darin Hayton. “There is, no doubt, considerable truth to that explanation, but it doesn’t help us understand why this particular story of women upending society and more specifically this particular visual trope remained popular. Whatever the reason, the ever youthful and attractive Phyllis was still riding around on Aristotle more than 400 years after overcoming the old philosopher.”

Comments

Post a Comment