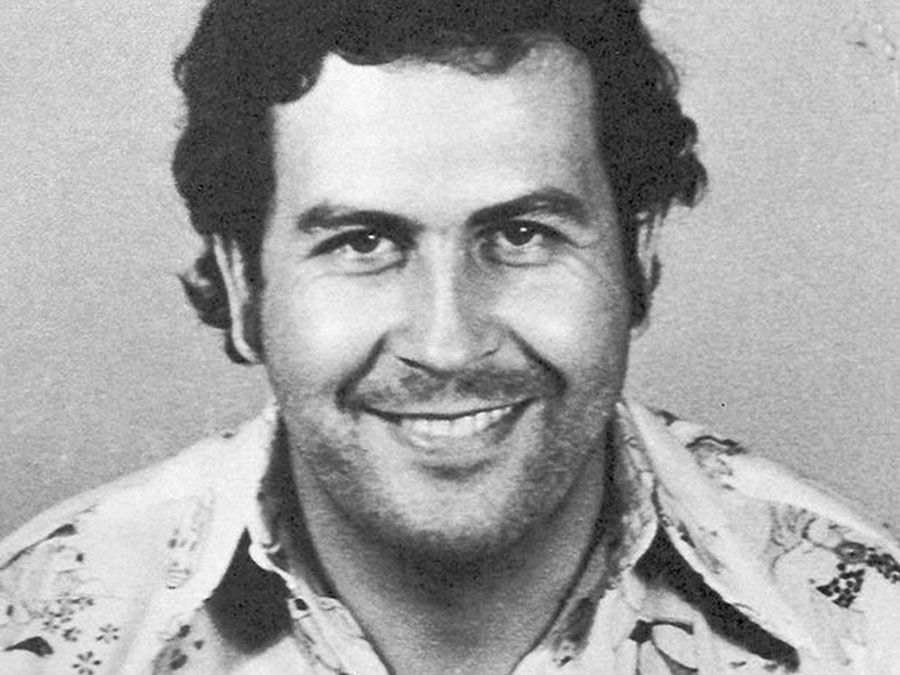

By 1991, Pablo Escobar had undergone a remarkable journey, starting as a car thief and then evolving into a small-time trafficker and kidnapper, ultimately earning the title of "the king of cocaine." However, this transformation came at a significant cost. Over the course of a decade, Escobar had accumulated numerous adversaries, including rival drug cartels and the government of various countries. Their collective efforts were gradually dismantling Escobar's life and empire. His rivalry with the Cali Cartel cost the lives of more than 300 of his associates and family. In addition, Escobar had seen fellow drug lords like Carlos Lehder extradited to the United States, and others like the Ochoa brothers had turn themselves in and go to prison. Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha, another Columbian drug lord, and his son had died in gun battles with the police. The final straw broke when his daughter Manuela was injured in a bombing at his residence.

Escobar wanted to surrender, but he worried that the Columbian government would extradite him to the United States—the only thing he feared the most. “Better a grave in Colombia than a cell in the U.S.,” he used to say.

Escobar entered into a dialogue with the government, and after six months of secret negotiation, agreed to go to prison. However, the prison would be built according to his own specification and at a location of his own choosing. He would have his own personal guards whose primary duty was not to prevent his escape, but rather to shield him from his enemies. Several other conditions were outlined, including the removal of Gen. Miguel Maza, one of Escobar's staunchest rivals. Another demand was that the Colombian National Police would be prohibited from entering a 12-mile radius around the prison. In return for these arrangements, the government pledged not to extradite Escobar to the United States. Escobar’s faux imprisonment, however embarrassing for the country, would help the government to get rid of a national headache. The arrangement also brought an end to the costs and resources invested in the relentless pursuit of the cartel leader.

Before Escobar formally surrendered, he began construction of his prison on the hills overlooking the city of Medellín. The high location afforded Escobar a bird’s eye view of the city that he virtually ruled for more than fifteen years. Escobar also appreciated the steep topography that would make it nearly impossible for the military or rival cartels to mount an air attack on the compound.

Escobar surrendered to authorities on June 19, 1991. The same day, he was transferred by helicopter to his newly built “prison”. The compound was called “La Catedral,” or The Cathedral because of its magnificence and the amenities it contained. Some called it “Club Medellin” or “Hotel Escobar.” The guards joked that it was not maximum security, but maximum comfort.

Satellite image of La Catedral.

La Catedral contained a football pitch and several buildings including a cinder-block home for the warden, seven guard towers, and a large building higher up on the slope for the prisoner. Escobar had his own suite with a rotating bed, a bathroom with a jacuzzi, a discotheque, a bar, a gym, a billiards room and a doll house for his daughter to play with whenever she came to visit him. He had cellular phones, radio transmitters and a fax machine that allowed him to conduct business, which at its peak brought his cartel $60 million dollars a day and oversaw control of up to 80 percent of the cocaine shipped to the United States. In addition, he had a powerful telescope installed that allowed him to look down onto the city of Medellín to the building where his family lived. Escobar would talk on his cell phone to his daughter and at the same time look at her through the telescope. The entire compound was surrounded by a ten-feet high fence and electrified barbed wire.

Also read: Hacienda Nápoles: The Home of a Former Drug Lord, Now a Theme Park

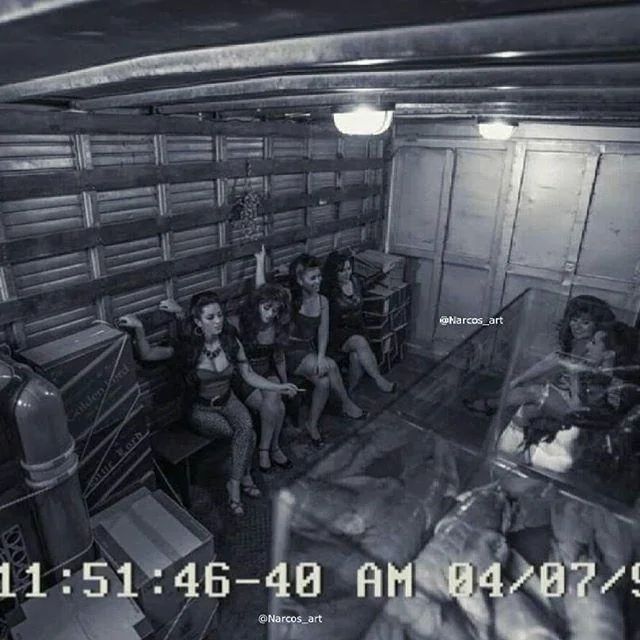

During the drug lord’s imprisonment, all sorts of people came to visit the Escobar every week. This included friends, business partners, politicians, beauty queens and prostitutes. Parties were commonplace. On his 42nd birthday, the kingpin hired some of the best chefs in Medellín and hosted a lavish banquet. He even hosted a wedding at his prison.

Escobar would routinely invite soccer players up to the prison for a game. Prior to the beginning of the 1994 World Cup qualifying run, all twenty-two players of the Colombia National team visited La Catedral, and took part in a friendly match with one of the world's most famous soccer clubs. The prison guards served drinks from the sidelines and later, acted as waiters in the bar.

Visitors and supplies to La Catedral were brought inside trucks, as this image from a security camera inside the truck shows.

Interior of Escobar’s mansion at La Catedral.

Interior of Escobar’s mansion at La Catedral.

Interior of Escobar’s mansion at La Catedral.

Escobar was free to do as he pleased, but when he ordered four of his lieutenants tortured and killed at the compound in a dispute over money, the government decided that things had gone too far and determined to move Escobar to a proper prison.

On 22 July 1992, one year and one month after Escobar had moved into his prison, the vice minister of justice, Eduardo Mendoza, went to meet Escobar to inform the cartel boss of the changes. Escobar was furious and threatened to kill Mendoza. When news of Mendoza’s hostage reached authorities, the Colombian National Army surrounded the prison and a firefight broke out between the army and Escobar’s guards. In the resulting confusion, Escobar managed to escape through an escape route that he had built into the facility during its construction.

Below: Video recorded by a journalist shows the compound immediately after his escape.

The Columbian government launched a massive manhunt. Despite thousands of soldiers and police combing the streets of Medellin, Escobar managed to evade capture for seventeen months, until 2 December 1993, when authorities caught up to him. The drug lord was shot dead while trying to escape.

La Catedral remained abandoned for many years. Scrap hunters stripped the place clean of anything valuable including bathtubs, pipes, tiles and roof materials. During his stay in La Catedral, Escobar had smuggled cash into his prison in milk cans. Rumors had spread that there were still cans buried in the compound containing millions of dollars, attracting treasure seekers who turned the place upside down in hopes of finding remnants of Escobar's fortune. Nothing was reportedly found.

In 2007, the government of Colombia loaned the 28,000 square meter property to a fraternity of hermetic Benedictine monks, who transformed the place into a "center of religious and cultural tourism"which now boasts a chapel, a library, a cafeteria, a guest house for religious pilgrims, workshops, an ecological trail, and a memorial dedicated to the victims of the cartel. The campus also includes a refugee for senior citizens who can't afford long-term care facilities in the city.

A gigantic mural with a picture of Escobar behind bars hangs on an original thirty-foot concrete wall that supports one of the new seniors buildings. Below his face is written, “Those who don't know their history are condemned to repeat it.”

References:# The Godfather of Cocaine, PBS

# Pablo Escobar’s Private Prison Is Now Run by Monks for Senior Citizens, The Daily Beast

# La Catedral: A Visit To Pablo Escobar’s Self-designed Prison, The Airship

Comments

Post a Comment