Sixty years ago the United States took upon itself a challenge—eradicate malaria from the entire country, all 3.8 million square miles of it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the nation’s leading public health institute, was borne out of this plan, and for the next four years the CDC devoted itself to the cause spraying DDT in millions of homes across the country. In just three years, malaria cases dropped from 15,000 in 1947 to only 2,000 in 1950. By the end of the next year, malaria was considered eliminated.

DDT’s effectiveness in killing mosquitos wasn’t known until 1939 when the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller discovered the chemical’s insecticidal action. Before that, controlling malaria was limited to proactive measures such as eliminating mosquito breeding grounds by drainage or poisoning with Paris green or pyrethrum.

Photo credit: Sangaroon/Shutterstock.com

At the turn of the last century, before malaria became a serious endemic threat to the United States, one Texas physician began experimenting with bats to fight malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

Unfortunately, for all his effort, not a single bat took the bait. Campbell spent the next three years making improvements to his bat tower out of his personal savings, but still no bats came. In desperation, he captured around 500 bats from another location and imprisoned them within the tower, hoping their squeaking would attract passers-by. That failed too. In outrage, Campbell tore down the tower and drove off the hundreds of English sparrows that had taken roost there instead.

Dejected with failures, Dr. Campbell went into recluse, suspended his medical practice and left his family to spend time alone in the mountains. There, he spent months studying bats in the wild, their behavior and their habitats. Armed with a wealth of information, Campbell returned and proceeded to build his next bat tower.

Municipal Bat Roost, erected by the City Council of San Antonia, Texas, March 17, 1916.

Campbell learned that bats preferred to roost near water, so he built his tower near Mitchell's Lake—a swampy low land where all of the city’s sewage flowed into creating the perfect mosquito breeding ground. From spring through fall, such is the onslaught of mosquitos that farmers from the surrounding land are forced to flee, leaving their crops to ruin and their livestock to suffer. In the spring of 1911, the year Campbell's new bat tower was built, seventy-eight of eighty-seven adults and children living around the lake had malaria.

Campbell finally got a taste of success. That summer, he returned to Mitchell's Lake and watched with satisfaction as hundreds of bats flew out of the tower in a long column taking a full five minutes to leave. Knowing that his bat tower had room for hundreds of thousands more, Campbell turned his attention to a bat-populated hunting lodge about 500 yards away. His goal was to drive all the bats out of the hunting lodge and into his tower. Campbell sought to achieve this by making the hunting lodge acoustically unfit to leave.

With the help of a friend, Campbell waited until the bats had left their roost for the night, and just before their scheduled return at the crack of dawn, he played a cacophony of clarinets, piccolos, trombones, drums and cymbals from a record at full volume. The bats with their sensitive hearing found the building too noisy, and as Campbell predicted, flew away. Campbell repeated the same musical performance at a nearby abandoned ranch house occupied by bats with similar results.

The following evening, Campbell went to his bat tower by the lake and timed their exit with his watch. This time the bats took nearly two hours to leave. Campbell was convinced he had succeeded in bringing the entire population of bats from both the hunting lodge and the abandoned ranch to his bat tower. In 1914, four years after the Mitchell's Lake roost was built, Campbell didn't find a single case of malaria among the families living around the lake.

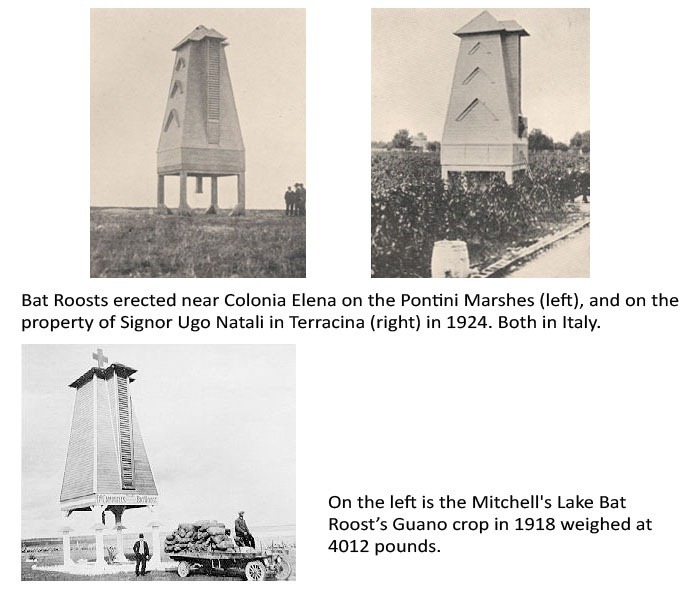

As word of his experiments spread, inquiry about bat towers began to come from all around the country and even as far away as Italy. Recognizing the tremendous results Campbell managed to achieve with meager costs, the City Council of San Antonio passed an ordinance making it unlawful for anyone to kill a bat within the city limits. The same year, the first city-funded Municipal Bat Roost was built in San Antonio. Killing bats eventually became illegal all across Texas.

The original Mitchell's Lake bat tower became a tourist attraction, and people began to arrive every evening to watch the bats leave. Picnic benches and seats were soon set up allowing visitors to watch the show in comfort. At its peak, the Mitchell's Lake roost contained over a quarter of a million bats.

From 1914 to 1929, a total of 16 towers were erected from Texas to Italy. Only about two or three survive, currently on private property. The Mitchell's Lake bat tower was pulled down in the 1950s when rabies hysteria gripped Texas and bats were taken off the State's protected species list.

One surviving bat tower, erected in 1918, stands near the town of Comfort, in Texas, at the country home of the former mayor. The shingled pyramid-shaped tower is 30 feet tall and raised on a concrete foundation, about seven feet off the ground, that allows guano collection from underneath. Guano is a great fertilizer, and a useful byproduct of the bat towers. In fact, the Mitchell's Lake bat tower averaged about two tons of guano a year.

The tower in Comfort is named “Hygieostatic Bat Roost”—the word Hygieostatic was invented by the mayor, Albert Steves, based on the Greek words hygiea (health) and stasis (standing). About a thousand bats currently reside there, although its population was once said to be around ten thousand.

The Hygieostatic Bat Roost near Comfort, Texas. Photo credit: Larry D. Moore/Wikimedia

A less successful bat tower at Sugarloaf Key in Florida. It was destroyed by a hurricane in 2017. Photo credit: donielle/Flickr